Like many of us, last weekend I had the honour and pleasure to meet with and listen to the Archbishop of York.

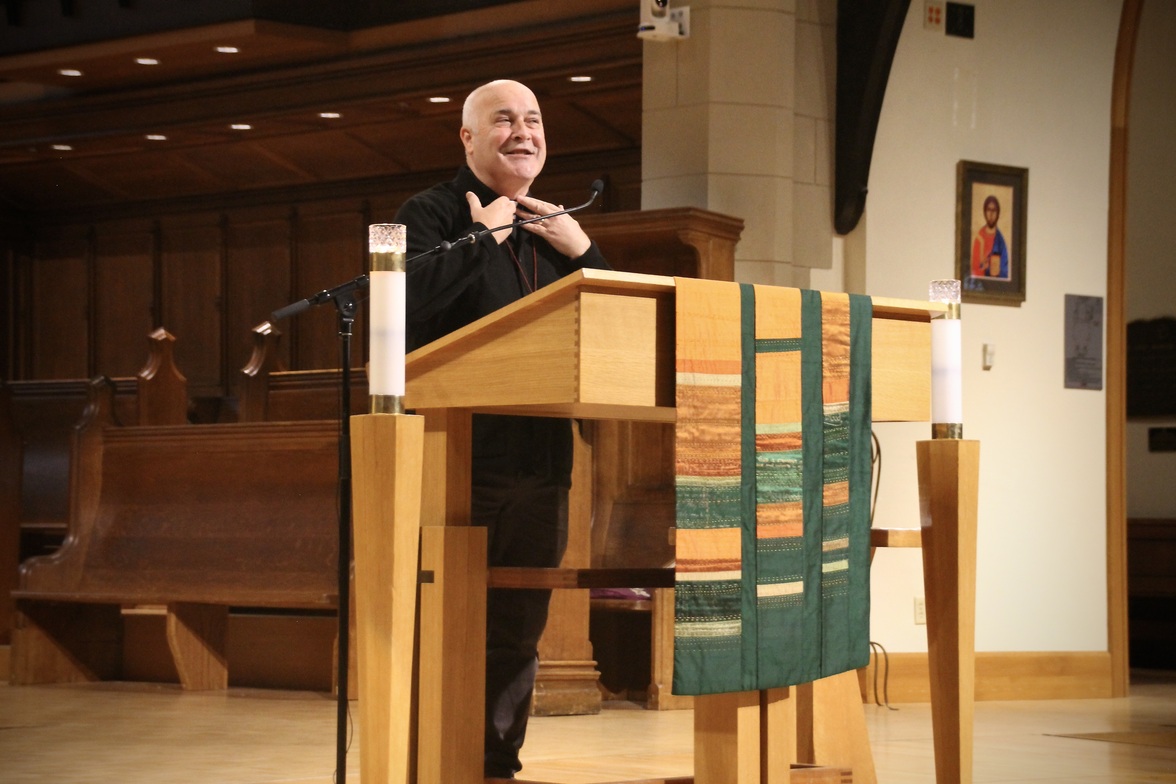

On the last leg of a cross-Canada tour, Stephen Cottrell offered a public lecture at Christ Church Cathedral on Saturday morning.

I vaguely remembered reading a notice about a 9:30 am coffee and muffin meeting for attendees preceding the lecture, but I thought I would just head straight for the main event. As it turned out, the archbishop, accompanied by his lovely wife Rebecca Cottrell and his chief of staff Mark Steadman, also attended the coffee klatch. There in the cathedral where my great grandparents Ruth and Arthur Jones, who met on the boat from Liverpool, were married in 1906, I learned that Rebecca was a ceramics artist and that she knew of my cousin Jonathan Chiswell Jones – a potter in Sussex - from that same Liverpool clan. It was all very familial.

Somehow, as a Canadian from a still very colonial culture, I thought it would all be more formal. I mean wow, the #2 man at the Church of England after the Archbishop of Canterbury wouldn’t possibly be noshing muffins with the likes of us. And yet he was.

The lecture, preceded by an introduction and prayer, by Bishop John Stephens, followed suit.

Archbishop Cottrell put everyone at ease instantly with a down to earth story telling style, full of self-deprecating humour, an unmistakable sincerity and a deep sense of spirituality. Just like the title of his latest book, Hit the Ground Kneeling: Seeing Leadership Differently, he led by example, exuding humility, humanity, and a genuine warmth. He offered no doctrinal absolutism, no sweeping answers, but rather questions that prompted his audience to contemplate their own paths as Christians. In the end, he came across as a man of faith who, like many of us, is still a seeker.

He began with a story about a chat with a barista at a Café Nero at Paddington Station, making me instantly nostalgic for the London hood where I stay when I’m doing PhD work at King’s College, (exploring the connection between ancient sacred sites and displaced Christian, Yezidi and Muslim communities in Iraq.)

The chat with the barista was about why he became a priest and the meaning of faith. The charming anecdote acted as a segue way that opened up the larger question of how we as Christians and Anglicans can be more open and welcoming. Using the analogy of a maternity ward – a place that welcomes expectant mothers 24/7- he invited us to explore ways that our churches can welcome seekers in a similar manner. He told the story of a Wednesday morning eucharist where he presided at his old parish that soon became a thriving community. This was an example, he said, of how we need to surrender rigid ideas of how things should be (i.e. people should come to church on Sundays) to embrace them as they are, fostering growth and connection.

Archbishop Cottrell then had us break into groups of 4 and discuss what our faith meant to us. I was delighted to meet some new friends, including an elderly English parishioner named Leslie, and the Bahamian-Canadian Reverend Tellison Glover from the Diocese of New Westminster. Leslie shared with us how much the church had evolved since he was a child. “In the old days,” he said, “There was a dress code. Men wore suits and ladies wore hats and gloves. And all the faces around me were white.”

“I wouldn’t mind a return to the dress code,” I replied, smiling at Reverend Glover. Later on, Leslie asked me for my card and said he was very interested in the plight of Christians in the Middle East. As it turned out, we discovered a mutual love for the books of William Dalrymple, especially From the Holy Mountain that explores ancient Orthodox Christian communities in the Middle East, like the one my Lebanese great-grandparents came from.

I mentioned that I came to church every Sunday because I felt a spiritual benefit from the ritual of worship, even if I didn’t always relate intellectually to the language of prayers and scriptures, and another man in our group said he felt the same way.

After our breakout groups, there was a sharing/ Q and A with the archbishop. I asked him about a question I often wrestle with – namely – how can I reconcile Christian values with what is going on in the Middle East, where the killing of civilians – including in my ancestral Lebanese village - is being funded by many Western, “Christian” nations: in essence, ‘how can I come to church and not feel like a hypocrite’?

I was impressed by the archbishop’s response. He listened quietly, really taking in the question and replied, “This is a tension that I live with every day. I’m not sure what the answer is.”

During a break he actually came to where I was sitting and kneeled down beside me, “I hope you didn’t feel disappointed that I didn’t answer your question,” he said. He went on to tell me of his deep concern for the situation in the region and of his son’s Lebanese girlfriend. It was a very human response, and it did not disappoint. Later I spoke with his chief of staff about ways I might help liaise with Christian communities in Iraq and Palestine, under increasing pressure as regional conflict continues.

When the lecture resumed, the archbishop went on to say that it’s important that we don’t just become self-absorbed in our worship but take action for social justice in the world. He also said that the meaning of “Give us this day, our daily bread” is about consuming only what we need, as a kind of spiritual practice for spreading peace and social justice in the world. He talked about the importance of increasing diversity in the church as “ecosystems flourish in diversity” and grow in on themselves and die in monoculture.

Another memorable point he made was that (only mildly paraphrasing) “Evangelism is not coercion or persuasion. It is accompanying someone on their journey, listening, and asking them what their questions are.”

I certainly felt accompanied and listened to and left with more questions than I’d arrived with. So, I decided to attend Sunday services the next day at St James’ Anglican Church, and continue my journey with the archbishop.

It was my first time visiting the gorgeous 1938 neo-gothic style church designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott that was apparently Arthur Erickson’s favourite building in Vancouver, and I’m glad I went.

As the morning light spilled into the church, the service led by Mother Amanda Ruston was beautiful and full of meaning. Appropriately, the first reading from the Revelation to John read by parishioner Elisabeth Kwan was all about Jerusalem. “…the holy city Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God. It has the glory of God and a radiance like a very rare jewel, like jasper, clear as crystal.”

When the archbishop delivered his homily in his richly adorned robes and impressive mitre, in the midst of the rather formal Anglo-Catholic service, once again it was down to earth and anecdotal, yet “clear as crystal.”

He told a story that many of us can relate to, about discovering a video of a past family Christmas in which he heard his late father call his name. When he heard him call out “Stephen,” he said, it was so full of love and recognition that he found it more moving to hear his voice than to see his image. This was how our relationship should be with God, he told us. We need to hear Him call our name and feel His love and recognition of our being.

Listening to this was so moving, (as someone still in mourning for a late parent), and so beautifully expressed our relationship to the divine and to each other, that I had to fight back tears.

After the service, there was another coffee klatch in the parish hall, where the archbishop, his wife and his chief of staff spoke to parishioners, including native elders. I ended up sitting next to Elisabeth who had done the first reading. Rather extraordinarily, it turned out she was an architect (I’m an architecture critic) and also a PhD candidate in Middle Eastern Studies at Cambridge. I soon had an invitation to her 50th birthday party/ celebration of her successful thesis completion (congrats Elisabeth! You are an inspiration!) at the church the following week. Was this some kind of magic? Or just an Anglican version of the old Sufi saying, “every meeting is a meeting with the self”?

Just like the reading about Jerusalem, which ultimately expresses the inner reality of the “holy city” as a place where people live in peace and harmony, a place where each person only takes what they need and shares fellowship with others, I felt the archbishop’s message resonate within me like a very rare jewel indeed.

What is living our faith really about? It’s about breaking down barriers between ourselves and others, between “us” and “them”; loving our neighbour as ourselves.

It’s not about pomp and circumstance or pecking orders (as much as we colonials can get bamboozled by all that) it’s about connecting with each other as part of the family of man.

I left the church asking questions about how I could break down these barriers within myself. I remembered the archbishop’s fond farewell and blessing as I left. Even though we had just met, he felt like family.