It was a quintessentially English May evening - gentle breeze, warm sunlight, lengthening shadows, an impossible number of songbirds singing their closing chorus from the trees.

Exeter’s Higher Cemetery, in the corner that holds the graves of Great War soldiers, was empty and peaceful, the greenery between the gravestones tidy, the gravestones themselves simple and unadorned.

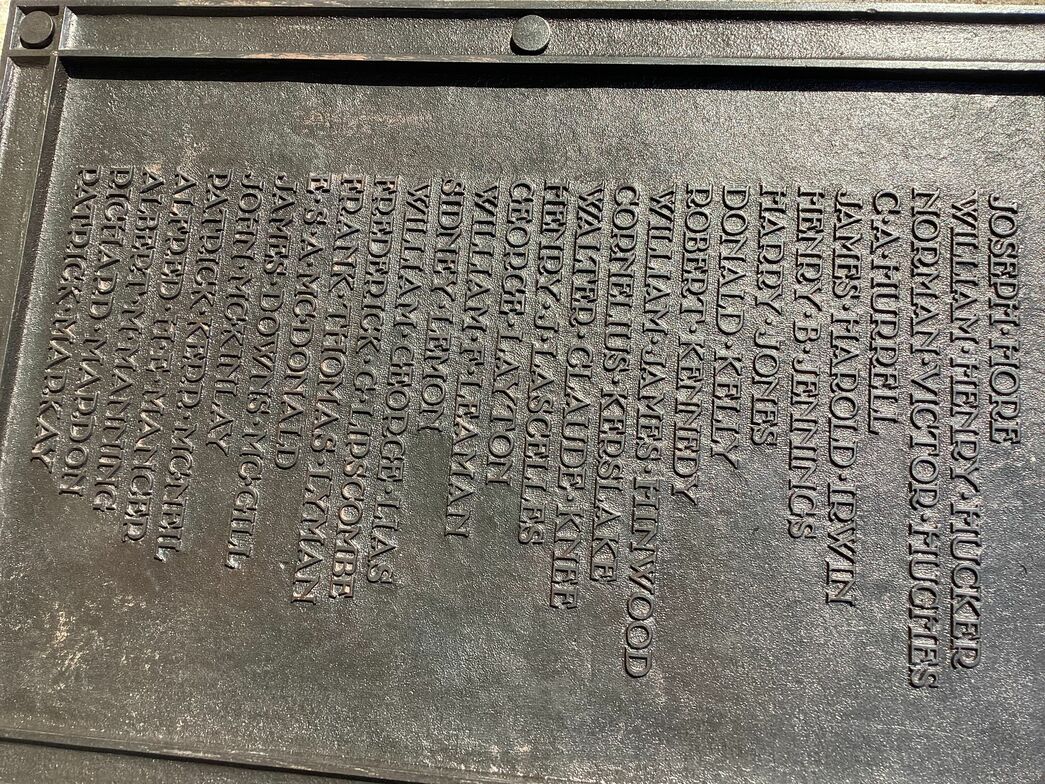

Except for one – that of N.V. Hughes of Canada, with its bouquet of long-stemmed yellow roses I had just placed there, almost 108 years to the day of Norman’s June 1, 1917 death in a war hospital in the city.

In telling Norman’s story, the part that I know, I must tell some of my own story, and of the practice of remembrance that continues to puzzle.

It was, maybe, early in 2014; much of the world was gearing up to mark the 100th anniversary of the August, 1914 start of what, sadly, we now call World War One, dispensing long ago with the unduly optimistic, once-and-done ‘Great War’ title of the time.

For many years, I had been a part of Christ Church Cathedral, which holds a number of war memorials, there for the seeing but so often, so easily overlooked.

When I started to look at what I had never really seen, I found two stained glass windows and one plaque, each dedicated to a church member who had died in that great war.

With the help of two enthusiastic research sidekicks, David and Nelson, one brilliant church archivist, Melanie, and a medical expert, Jacky, biographies emerged from the historical twilight. I bound them together in a one-act play, Duty Calls – Men of Christ Church Go to War, performed three times over the years, with its premiere in November, 2014.

The first two biographies were easy - the plaque in the military alcove belongs to Lieutenant-Colonel William Hart-McHarg, a lawyer, a bachelor, and a big wheel in the smallish city that was early 20th-century Vancouver. As commander of the 7th Battalion of the First British Columbians, he lived through the war’s initial, terrible gas attack on April 22, 1915, beginning the 2nd Battle of Ypres. He lost his 46-year-old life to a single bullet the next day while on daylight reconnaissance.

Today, he has a well-documented place in the BC Regiment’s Vancouver museum, and in history books.

The second memorial, a finely-made window of a first war soldier on the east wall, is dedicated to Lieutenant Harold Owen, son of the church’s rector, the Rev. Cecil Owen. Harold, 22, was also killed by a single bullet, while on reconnaissance just before midnight on January 30, 1916.

Harold had been a golden youth, in medical and seminary studies in Toronto, headed toward a life as a medical missionary. His father, Cecil, a confident public figure and the inheritor of family wealth, was another big wheel in the Vancouver of the time.

Harold, like the lieutenant-colonel, signed up shortly after Great Britain’s Aug. 4 declaration of war. Cecil joined the army as a chaplain the next spring - he was there at the Front for his son’s battlefield funeral. Reminiscences of and letters from both men abound in church, civic and military archives.

But that third memorial – an east-wall stained glass window of Jesus calling fishermen Andrew and Simon to be disciples, with a St. Andrew cross at the bottom, given for Norman Vincent Hughes? Who was Norman?

It took some looking, for sure, through century-old city directories; micro-filmed newspapers; school, university, and church records; military files in Library and Archives Canada.

There was no sign of personal letters, but we did find Norman in the end - “our Norman” as we started calling him - and we found a young man as ordinary and as special as any private in every army in any age.

He was born November 17, 1897 in New Westminster, an only child to his parents, Joseph Henry and Mary Hughes. J. Henry, variously described as an electrician and a mechanic, was, by 1914, a foreman with the B.C. Electric Railway Co. and the owner of a custom-built house overlooking English Bay that still stands. Comfortably off, certainly, but probably no one’s idea of a big wheel.

Norman, evidently, enjoyed Anglican church life. As a Sunday school stalwart from the age of three and a Bible class regular, he gave himself wholeheartedly to leadership in the Brotherhood of St. Andrew, a North American church group for boys and young men.

In Duty Calls, he tells us of his frustration as war recruitment swelled in Aug.,1914. “I was 16 years old. There was no question of lying about my age to sign up. My parents wanted me to stay in school. And, anyway, there were lots of men enlisting. Enough men. My turn wasn’t ever going to come.”

That autumn, Norman enrolled as an arts student in the first-ever class of the brand-new University of British Columbia, expecting to graduate in 1918.

“It meant a lot to Mom and Dad to see their only child get the education they never had a chance at,” he says. “But I wanted to be part of the war, and they needed more and more men.”

So many men that university battalions were formed across western Canada early in 1916. On March 29, “I signed up. I didn’t even write my final exams. UBC gave an automatic pass to anyone who was enlisting.”

Norman’s attestation paper attests to his 6-foot height, his brown hair, his brown eyes. Tributes suggest he was quiet, conscientious, sweet-tempered.

“Three hundred of us were marching and training, with football and baseball and parades to Kits Beach to go swimming. I wrote my officer exams in May and passed. That could have made me a lieutenant, just like Harold. But, by then, the army wanted men to have battle experience before they were commissioned.”

It was full-on ahead to that experience - from Vancouver to Camp Hughes in southern Manitoba in June for basic training, then to England in November, and to France in February,1917, just in time for the Apr.,1917 nation-building battle for Vimy Ridge.

What was Vimy for Norman? That’s a blank page, but, after his company rested from the battle, his story picks up again on May 4, 1917, back on the line. “It was a bright, moonlit night. I was on sentry duty when the machine gun found me, right here in my side. I was in hospital in France for two weeks. I couldn’t move my legs.”

“Then I was shipped across the Channel to Exeter where the sheets were clean and the nurses were kind. I couldn't even feel my legs. I got sicker and sicker. I was 19 years old. I died on June 1 at 7:10 p.m.

“Dad came from a big Irish family in Ontario. He had 13 brothers and sisters . . . that window must have cost a lot of money. . .

“I guess he and Mom really didn’t have anyone left. But, that window – well, they brought me home didn’t they?”

Did Norman’s Canadian parents ever visit his English grave? That seems unlikely, given their time and place. They put their grief and love into a stained glass window in their church – would they have reached out and touched that window again and again, finding solace and even peace? I hope so.

But what was I doing, putting flowers on a grave of a long-dead teenager, who was really nothing to me? Except that, without anyone’s permission, because there was no one to ask, I had told what I knew of his story - and surmised the rest - in public to the public. And many of the people who heard that story told me it mattered.

On that May evening, then, maybe I wasn’t so much remembering as saying, quite simply, thank you.